This Women’s History Month, we highlight two phenomenal Black women activists. These women are working to advance police reform not only to save the lives of Black people but to bring attention to an often overlooked and rarely examined issue: how police violence affects Black women’s lives.

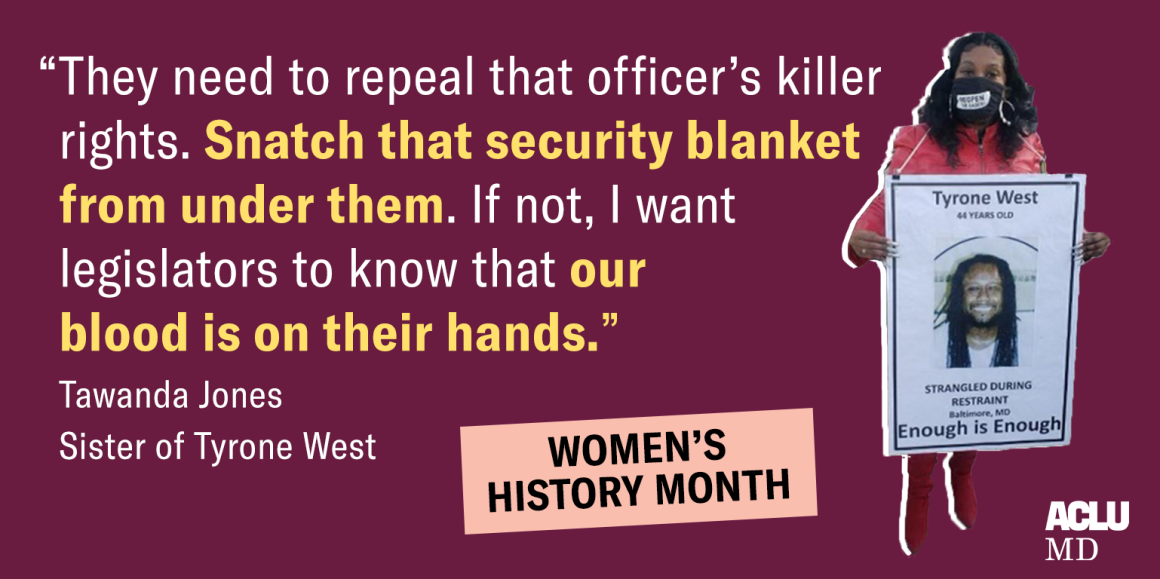

“My brother Tyrone West was a father,” said Tawanda Jones. “He was also my best friend, the glue to my family. Everybody loved and adored him.”

On July 18, 2013, multiple officers chased and beat Tyrone West until they eventually killed him. Tawanda remembers that her brother was an aspiring artist who could paint and draw very well. Her family dreamed that he would open his own art studio one day.

“I can still hear his voice, see his great big smile, remember the way he laughed and joked,” said. Tawanda. “Every moment that I got a chance to spend time with him and talk to him was a great moment.”

When those police officers stole her brother’s life and took him away from his family, that pain drove Tawanda’s activism and motivated her to ensure that other families do not have to go through the same tragedy and injustice she went through.

“When they killed my brother, it smacked the life out of me,” said Tawanda. “The pain hits differently when it’s your loved one. That pain hit me and knocked the life out of me. It pushed me down this road. It was a road that I never asked for. This is my new life now.”

What Tawanda advocates for every day is accountability. “I don’t care how long it takes,” said Tawanda. “I am my brother’s keeper. I am always going to speak up, not just for my brother, Tyrone West, but for all the victims of police brutality. What happened to my brother shouldn’t have never happened. To no one’s loved one. It did not take 11-15 people to beat one unarmed man, to beat, stomp, pepper spray, and tase him. One day, we will get accountability.”

In the past year, 1,127 people have been killed by the police in the United States.1 That means hundreds of thousands of partners, siblings, children, friends, parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and many more loved ones are affected by these killings.

Tawanda said, “People that are left behind are the new victims because when you kill their loved ones, their life will never be the same.”

Police killings cause extreme emotional distress and pain to the loved ones who have to live their life without having, holding, or speaking to their loved one(s) anymore. Tawanda said: “At the same damn time while we are suffering, we still got to pay our dues to society. We still got to go to work. We got to go to work traumatized and tore up.”

The way to begin to prevent more police killings is by holding officers accountable, which means repealing the Law Enforcement Officer’s Bill of Rights, a law that gives police officers special due process rights that shield them from the consequences of their brutal and deadly actions.

Tawanda is pushing for the full repeal of this dangerous law. “They need to repeal that officer’s killer rights,” said Tawanda. “Snatch that security blanket from under them. If not, I want legislators to know that our blood is on their hands.”

Not only do Black women face the pain of losing a loved one to police violence, but they are also directly targeted themselves. Black women are arrested, have experienced use of force, and are killed by police at disproportionately higher rates than women from any other race.

Last year, the New York Times reported that since 2015, police have killed 48 Black women and only 2 officers have faced charges. These numbers are part of a systematic pattern of police violence against Black women. This system of white supremacy voluntarily fails to hold officers accountable for their lethal actions and promotes violence against Black people.

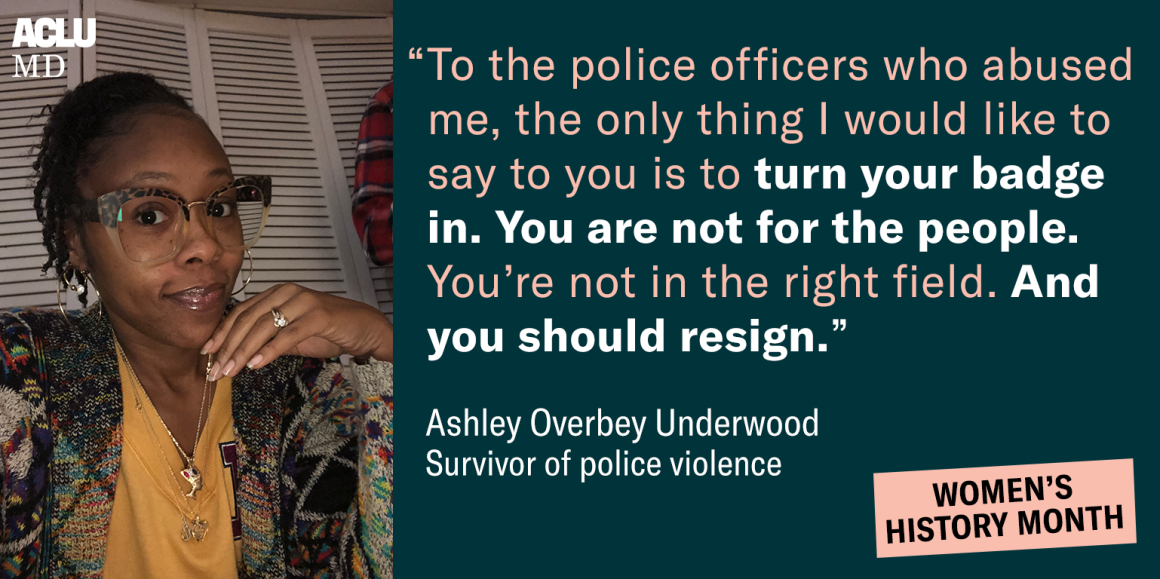

In 2012, Ashley Overbey Underwood called the Baltimore City Police Department to report a robbery at her apartment. Three sets of police officers were dispatched to her apartment in the hours that followed. One of them, Officer Fred Hannah, forcefully entered and began searching her apartment without her permission.

When Ashley asked him to explain what he was doing, he became violent and aggressive. Another officer, Martin Richardson, came soon after, and together the two police officers began to beat, tackle, choke, tase and handcuff both Ashley and her mother. They beat Ashley so badly that she needed to be transported to the hospital.

Ashley’s experience traumatized her. “I have PTSD from it,” said Ashley. “Every single time I have to come in contact with an officer, my hands are sweating, my heart is racing, and my stomach is hurting. They don’t even have to have said anything to me, but this is the feeling I get, just being in their presence.”

Ashley doesn’t even call the police anymore when she needs help. Calling police officers is her last resort. Ashley said: “If there were any good cops, the bad cops would be being held accountable for all of the things that they do to us. All of the misconduct. All of the abuse. Yet, they do the very opposite of that every single time.”

After Ashley was beaten and hospitalized, she was then jailed for 24 hours, and charged with six counts of assault on an officer and one count of resisting arrest. Thankfully, all charges against Ashley were dropped and she successfully sued the Baltimore Police Department for wrongful arrest and unwarranted physical abuse.

However, as a condition of settling the case, the city and police department required Ashley to agree to a non-disclosure agreement, also known as a “gag order,” that silenced her from talking publicly about her experience. Ashley was abused again by the police when half of the settlement was taken away just because she defended herself in comments on a blog – incited by false charges against her by the City Solicitor – where members of the public disparaged her character for suing the police and accepting a settlement, without any understanding of the level of excessive and illegal force used by the police. The Baltimore Police Department punished her by withholding half of her settlement amount for exercising her right to free speech.

Nevertheless, she won once again in court. The court case, Ashley Overbey and Baltimore Brew v. BPD resulted in a precedent-setting ruling from a federal appeals court holding that gag orders, including Ashley’s, which silences survivors of police violence for money, are unconstitutional and therefore unenforceable.

Even though this instance of police violence happened years ago, Ashley still has lingering questions. “I want to know why still,” said Ashley. “I really would like to understand why that night went anything like it did. To the police officers who abused me, the only thing I would like to say to you is to turn your badge in. You are not for the people. You’re not in the right field. And you should resign.”

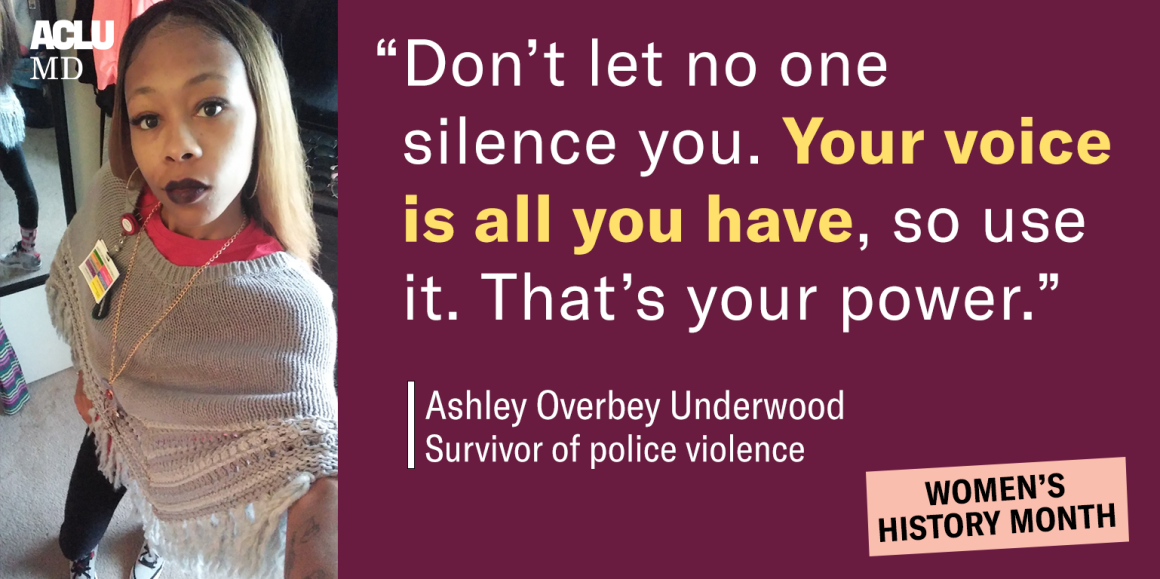

Police officers are public servants and should be serving their communities. Ashley said: “We pay their tax dollars. Our tax dollars pay their salary so they should be taking care of us. We shouldn’t fear them. Don’t be bullied into thinking you can’t fight back.”

As an activist and a mom of four, Ashley hopes that her advocacy for justice helps others fight for their own justice as well. “To anyone who is in my position, all I can say is stand your ground. I don’t care if everybody is against you. As long as you’re being honest, never give up the fight and never let them get away with abusing you because that is not what they are here for. Don’t let no one silence you. Your voice is all you have, so use it. That’s your power.”

What these two activists hope to see in the future is a future of freedom and true equality for all. The community is not asking but demanding that we reimagine policing to save Black people’s lives.

Ashley said, “I want the same thing everyone else wants, which is for everyone to be treated equally and fairly, for the laws to be reformed, so that it’s not a system that is built against Black people.”

Similarly, Tawanda wants to see an equitable system. She said: “I want to see the same thing that my dying ancestors wanted, who for over 400 plus years were hung from trees and fought. I want to see what real freedom looks like. I want to see a day where we can feel how it feels like not to worry, how it feels to have a life of freedom, where you can wake up and the only thing you’re worried about is how to pay bills or what you’re going to cook tonight. Black people have to worry. I can’t get sleep at night until both of my grown children are back at home in their house or at home at my house. I can’t get no sleep until they’re home safe.”

To make these hopes a reality, we need your advocacy. Join us in the struggle to end police violence and to reimagine policing.

Tell your legislators that we need cops out of schools, a statewide use of force law, to get rid of the Law Enforcement Officer’s Bill of Rights, give back local control of BPD to Baltimore City, and make investigations into police officers transparent.

1Mapping police violence. (n.d.). Retrieved March 06, 2021.