“What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again, and again?” Were three simple questions President Lyndon B. Johnson asked in 1967 when he created The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders that July.

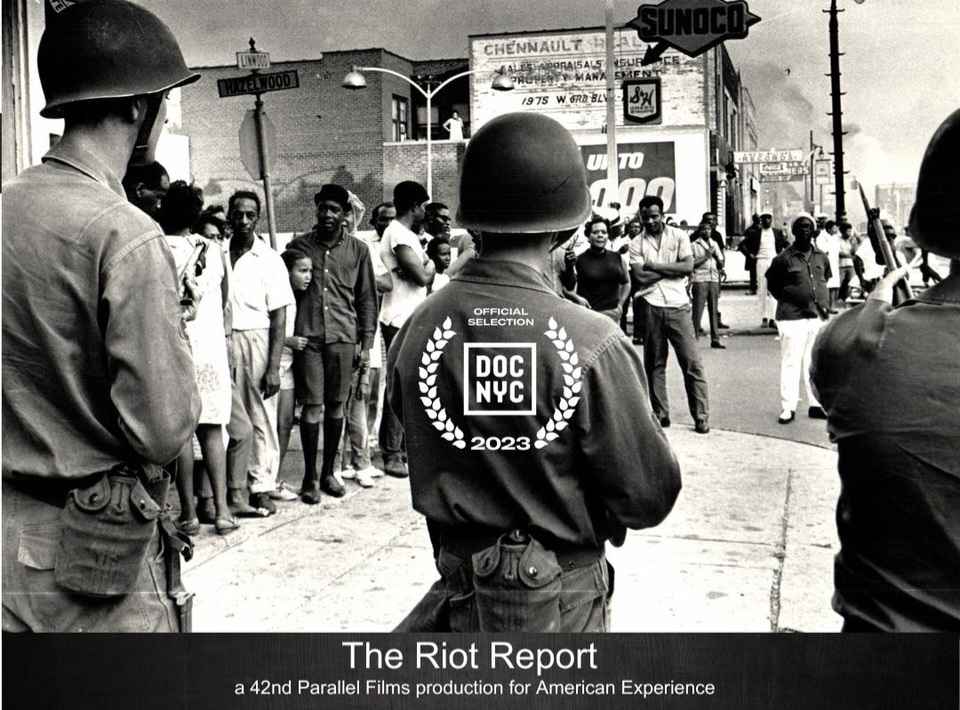

More commonly known as the Kerner Commission, named after its chairman, former Illinois governor Otto Kerner, the 11-member commission was tasked with investigating America’s massive “rioting” problem. The goal was to provide preventative solutions to the dozens of uprisings that were erupting across American cities between 1964 and 1967, and in later years to come. Cities like Los Angeles, Detroit, and Newark were literally on fire in a warlike scenario not seen since the Civil War. Destruction, looting, and violence between police and Black neighborhoods had reached peak levels.

President Johnson’s questions seemed simple enough, but the task of answering them 57 years later remains complicated, though not impossible. All this was before my time, but that didn’t nullify me from its rippling effects.

Reformation and advocacy have long been cornerstones of my life. Which by force or by choice led to my involvement in many protests and uprisings, most notably on a college campus and early into my career. However, it was while I was a graduate student at Morgan State University’s School of Global Journalism and Communication in Baltimore, Maryland where I first became aware of the Kerner Commission.

I was writing a paper on the 50th anniversary of the Commission, assigned to me by my journalism professor, Dr. Rodney Carveth. I couldn’t have known it at the time, but four years after I submitted that essay, I’d be an associate producer on the telling of the story on PBS.

Directed by the critically acclaimed documentarian Michelle Ferrari, and with TV’s most-watched history series American Experience and the great minds at 42nd Parallel Films, The Riot Report analyzes the story of President Johnson’s Kerner Commission. It looks deeply at race relations among Black and white people, and police violence. And it examines the political ramifications of social retributions during a turbulent time in America’s history.

Collaborating with the likes of distinguished historians and professors such as Khalil Gibran Muhammad, Elizabeth Hinton, Steven Gillion, and many others, my job as a producer came with many hats. Facilitation, hiring, location management, archival, etc. Roles often vary from production to production but to put it briefly, a producer ensures that everything that can be done, has been done, so production can go as seamlessly as possible.

While I had worked on similar projects before, this documentary was particularly special given my fascination with the subject matter, which paired nicely with my utter excitement and the mental challenge that it required.

As I was finishing up my master's in Baltimore, COVID-19 happened, and then May 25, 2020, happened -- the police murder of George Floyd. Because of the virus, I was unable to walk across the stage that year, but that didn’t stop me from running into the streets. In the thick of these rebellions, I made it a mission that summer to not only write and study but also participate in this reckoning.

This on-the-ground insight was indispensable when I was eventually offered a role in the production of The Riot Report. Experiences from political participation and protest cannot be undervalued, and what I found most interesting in researching the Kerner Commission of 1967 and comparing it to what was happening in 2020, was that this commission’s findings were not just a report, it was a forecast.

The protests from that summer of 2020, often referred to as the “Racial Reckoning,” was a climactic global response to the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmuad Arbery, Rayshard Brooks, Tony McDade, and so many others by the hands of police or white vigilantes. Just like the acts of resistance that occurred across American cities in the 1960s, this was the modern-day uprising. Black Americans and other People of Color had reached a boiling point paradoxically separated and shared across time by over 50 years -- and a history lesson the nation had not yet learned or refuse to.

For some, these acts of resistance were considered riots, which granted a negative public perception. But that’s a misnomer – these movements were rebellions. Moreso when you consider the United States itself was born from a successful uprising against British control. The difference is a rebellion presumes to know the political motivations of everyone involved, but a riot does not necessarily preclude political motives for the actions. Historian Elizabeth Hinton, featured in the documentary said it best “the word riot was nothing less than a racist trope applied to events that can only be properly understood as rebellions — explosions of collective resistance to an unequal and violent order.”

Black rebellion has always had a future in America in large part because it has a long history. The Racial Reckoning was a political reaction to the senseless murder of Black bodies and the systems of inequality that enables such murder. The systems in place promote an insidious merry-go-round that has transcended generations and claimed countless Black lives from Emmitt Till in Mississippi to Arthur McDuffie in Florida to Tyrone West, Freddie Gray, William Green, Anton Black, and too many more here in Maryland.

After seven months of investigation, the Kerner Report was released on February 29, 1968, with recommended changes to the institutional and systemic racism that plagued the United States. Some of these recommendations included developing urban and rural poverty areas, opening the existing job structure and creating new jobs in the private and public sector, encouraging business ownership in Black communities, improving community school relations, supplying housing for families with lower-income, work training and incentives, expansion of higher education opportunities, and many others.

Interestingly, the report also mentioned the need for change in police operations in Black communities to ensure proper conduct by individual officers and to eliminate abrasive practices, including “indiscriminate stops and searches” as well as greater “mechanisms for resolving people’s grievances against police.” Uncoincidentally, these same recommendations remain relevant decades later, with laws like the Maryland Police Accountability Act of 2021 and the creation and maintenance of local police accountability boards and civilian review boards.

In addition to these recommendations, the Kerner Report also left us with a grim warning -- "our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal" – and stated that this was the underlying cause of such rebellions. Martin Luther King, Jr. said that “a riot is the language of the unheard and what is it America has failed to hear?” Dr. King was assassinated 36 days after the report’s release.

The proposals by the commission may not be all that is needed to fix our deeply rooted problems, but it’s a start a half-century in the making. If we are serious about making sure fewer rebellions are needed, to have real public safety for all, we need to invest in the communities that are most harmed by white supremacy. We need to take action not only in the street but also in the legislature and courts, as a community and as a people. We need to tell the story; these riots did not start themselves.

My experience in life was a conduit for my experience and labor on this documentary film. Even though it’s curtain call for that project, I can’t help but wonder what else the report might predict in the decades to come, and if we have the resolve to stop it. With this information now, how do we answer for ourselves President Johnson’s original question? We know what happened. We know why it happened. And yet, we continue to find ourselves struggling to prevent it from happening again, and again.

For more information, watch The Riot Report, streaming on American Experience on PBS.