VICTORY! MARYLAND REPEALS ITS BROKEN DEATH PENALTY SYSTEM

The death penalty in Maryland was broken - costly, biased and risked executing the innocent.

MARYLAND MARCHES TOWARD JUSTICE: We in Maryland are better off for having left the death penalty in the past. Why? Because when this broken system was in place. The danger of executing the innocent was too high

- In 1993, Kirk Bloodsworth was awarded $300,000 for wrongful punishment. After eight years on death row, DNA evidence proved that he was innocent. Despite the testimony of alibi witnesses, Bloodsworth was sentenced to death in 1985 for a tragic rape and murder. In 1986 his conviction was reversed on grounds of withheld evidence pointing to another suspect; he was retried, re-convicted, and sentenced to life in prison. In 1993, newly available DNA evidence proved he was innocent, and he was released after the prosecution dismissed the case.

- Anthony Gray was threatened with the death penalty for a 1991 rape and murder he did not commit. With borderline mental retardation, Gray confessed to avoid execution and served seven years of a life sentence. DNA testing later exonerated him and found the real killer.

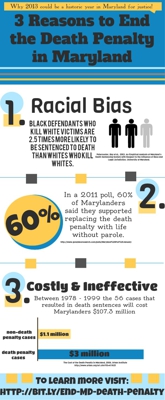

The laws did not reflect the values and views of a majority of Marylanders.

- By a margin of 60 percent to 33 percent, Marylanders say life without parole is an acceptable alternative to the death penalty, according to a January 2011 poll by Gonzales Research & Marketing Strategies.

- Maryland Governor Martin O'Malley is a strong and public proponent of death penalty repeal.

The death penalty was failing victims' families

- To be meaningful, justice should be swift and sure. The death penalty is neither. It prolongs pain for victims' families, dragging them through an agonizing and lengthy process that holds out the promise of an execution at the beginning but often results in a different sentence in the end. Meanwhile, it showers scarce resources on a few cherry-picked cases while the real needs of the vast majority of victims' families are ignored.

- The Maryland Commission on Capital Punishment made TWO recommendations: Repeal the death penalty and use some of the savings to improve and increase support for the surviving families of homicide victims.

- Some victims want the death penalty. Some don't. But increasing numbers of victims and victims' advocates agree that in trying to adjudicate capital punishment, it is the survivors of homicide victims that lose out. Proponents of keeping the death penalty argue that it should be up to the individual families to decide whether they want to endure the long process.

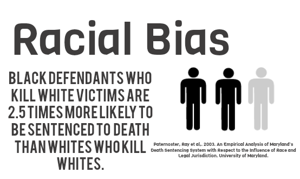

The death penalty in Maryland was racially biased

- A study commissioned by Governor Martin O'Malley found that black defendants who kill white victims are more than twice as likely to receive death notifications as black offenders who kill black victims.

- Black defendants who kill white victims are 2.5 times more likely to be sentenced to death than whites who kill whites, and they are 3.6 times more likely to be sentenced to death than blacks who kill blacks.

- Three years before the Paternoster Study was released, two judges of the Maryland Court of Appeals, including its Chief Judge, concluded that there is a "strong argument" that "there is little or no rationality underlying the actual imposition of the death penalty in Maryland, and that the penalty disproportionately falls on poor African-American males accused of murdering white victims." This was based on over two decades of judicial experiences with the death penalty.

- Further, studies like that commissioned by the Governor of Maryland found that "black offenders who kill white victims are at greater risk of a death sentence than others, primarily because they are substantially more likely to be charged by the state's attorney with a capital offense."

- In Maryland for many years almost all of the death cases came from predominantly white Baltimore County, and almost none from predominantly black Baltimore City. In 2002, Baltimore City had only one person on Maryland_s death row, but suburban Baltimore County, with one tenth as many murders as Baltimore, had nine times as many on death row. (L. Montgomery, Md. Questioning Local Extremes on Death Penalty, Wash. Post, May 12, 2002)

- In 2008, the Maryland Commission on Capital Punishment, established by the state assembly, recommended that the state repeal capital punishment due to the real possibility of the execution of innocent persons, and due to racial disparities. One year later, after nearly passing abolishing legislation, the Maryland General Assembly passed and Gov. Martin O'Malley signed the tightest death penalty restrictions in the country, limiting capital cases to those with biological or DNA evidence of guilt, a videotaped confession, or a videotape linking the defendant to a homicide.

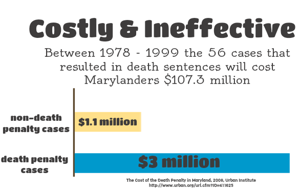

The death penalty was a burden on taxpayers

- One capital prosecution resulting in the death penalty costs our state about $3 million, that is $2 million more than the alternative, life without parole

- In Maryland, a comparison of capital trial costs with and without the death penalty for the years concluded that a death penalty case costs "approximately 42 percent more than a case resulting in a non-death sentence."

- Between 1978 and 1999 there were 56 cases resulting in a death sentence, and these cases will cost Maryland citizens $107.3 million over the lifetime of these cases.

- In addition, the 106 that did not result in a death sentence are projected to cost Maryland taxpayers an additional $71 million. In addition, the Maryland Capital Defender's Division cost $7.2 million. Thus, we forecast that the lifetime costs of capitally-prosecuted cases will cost Maryland taxpayers $186 million.