People Who Were Imprisoned Are Leading the Fight to Free the Vote

“I just think it's important when we consider voting is that folks who are in prison or jail don't lose their humanity.” –Nicole Porter, director of advocacy of The Sentencing Project

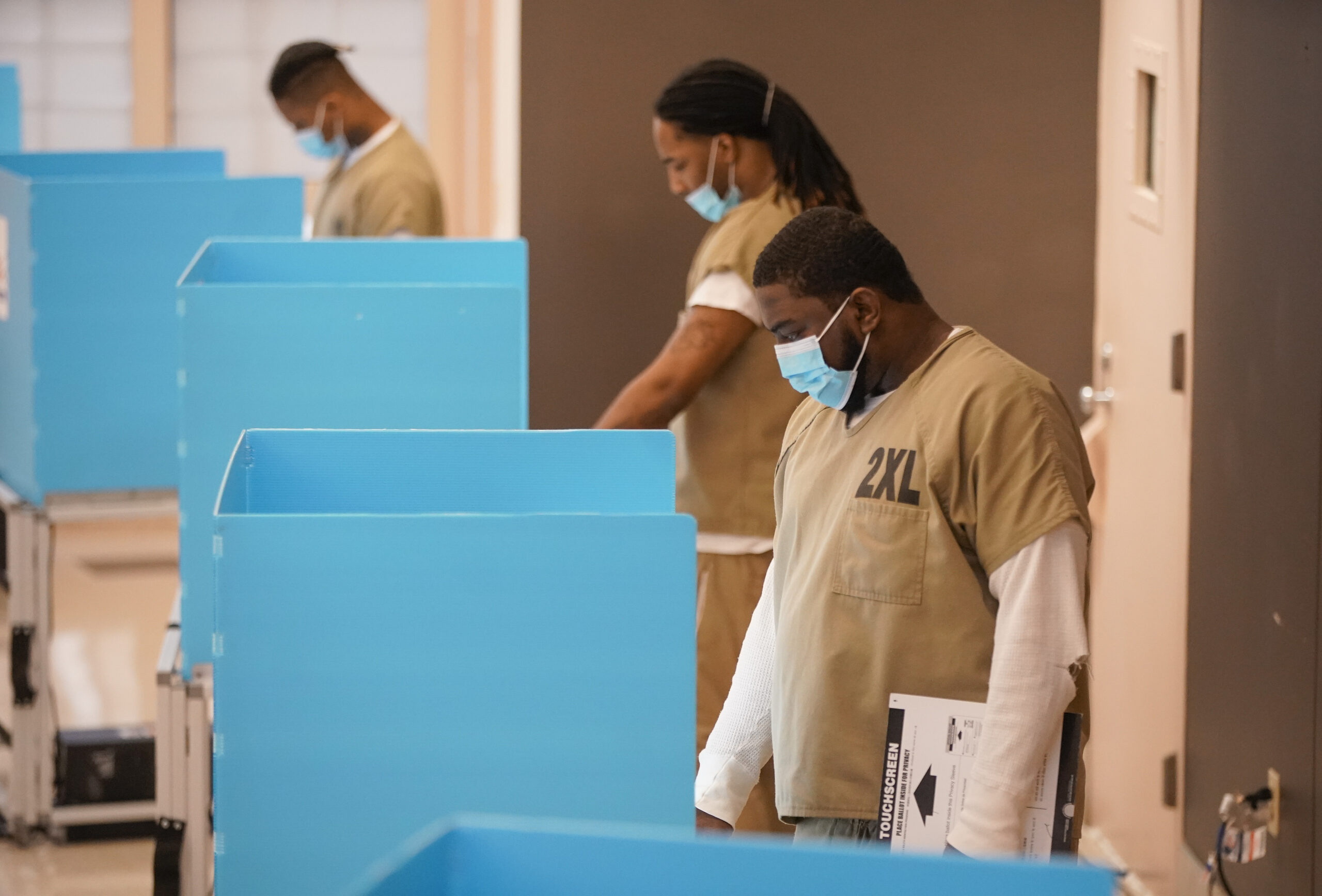

Voting is a part of what makes you feel American, a part of society, an equal human being who has a say in the policies that affect your community. The Free the Vote documentary not only shows why voting is a racial justice issue but also highlights the voices of people who have experienced what it is like to have their vote taken from them.

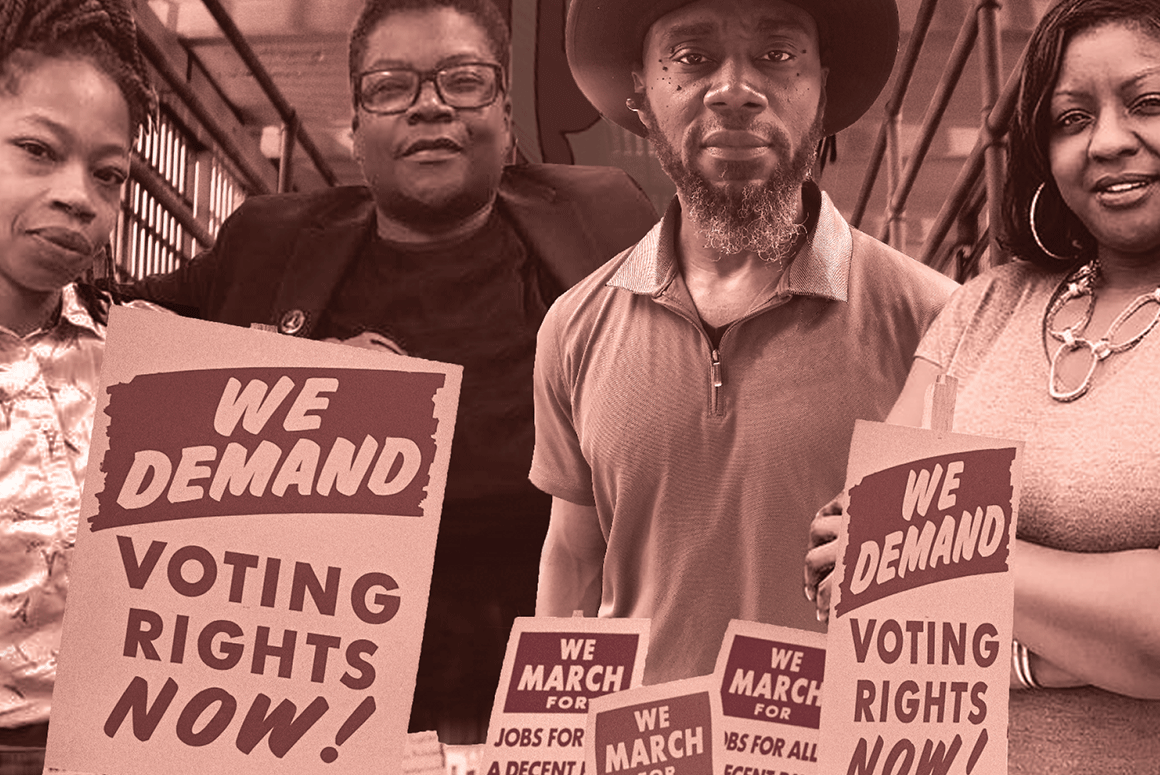

(Left to right: Nicole Hanson Mundell, Monica Cooper, Earl Young, Qiana Johnson)

Monica Cooper runs a nonprofit called the Maryland Justice Project. Growing up in her family, generation after generation, it was instilled in Cooper that voting was a part of her civic duty. When her right to vote was taken from her when she was incarcerated, it affected Cooper deeply.

“All my power was gone,” said Cooper. “All my rights was gone. I couldn’t eat when I wanted. I couldn’t walk to the store. I couldn’t watch television when I wanted to. Everything. Every bit of my power was gone. So, I dreamt about voting because it always made me feel powerful. It made me feel like I could control my destiny. Being a Black woman in this country and growing up in West Baltimore, as a child, I often felt like I had no power.”

Before 2016, people who were incarcerated for felonies could not vote in Maryland even if they were returning citizens. After coming home from being incarcerated, Cooper found that she was still unable to vote. “I wasn’t able to vote in the presidential election for President Obama. I was really disappointed.” What could have been a very empowering action for Cooper after she returned to her community was stripped away from her.

Cooper said: “I think that people should care about voting rights for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people because you have thousands and millions of people who are being left out of the conversation and decisions.”

In 2016, the law in Maryland changed so that people who were previously incarcerated for felonies could vote upon their release. However, people who are currently incarcerated for felonies still can’t vote.

Keeping the vote from people who are incarcerated breaks important ties that they have with society. Earl Young, a member of the Lifer Family Support Network and a Marylander who was incarcerated for more than three decades, said, “Not having a vote, not having a voice, we felt like we were part of the process but removed from the process.”

Even though Young could not vote himself when he was inside, he still used his voice to hand write letters to politicians on policy issues that were important to him. “I watched the ex-felon vote bill,” said Young. “All I thought about, all individuals like me thought about, was we can’t squander this opportunity.”

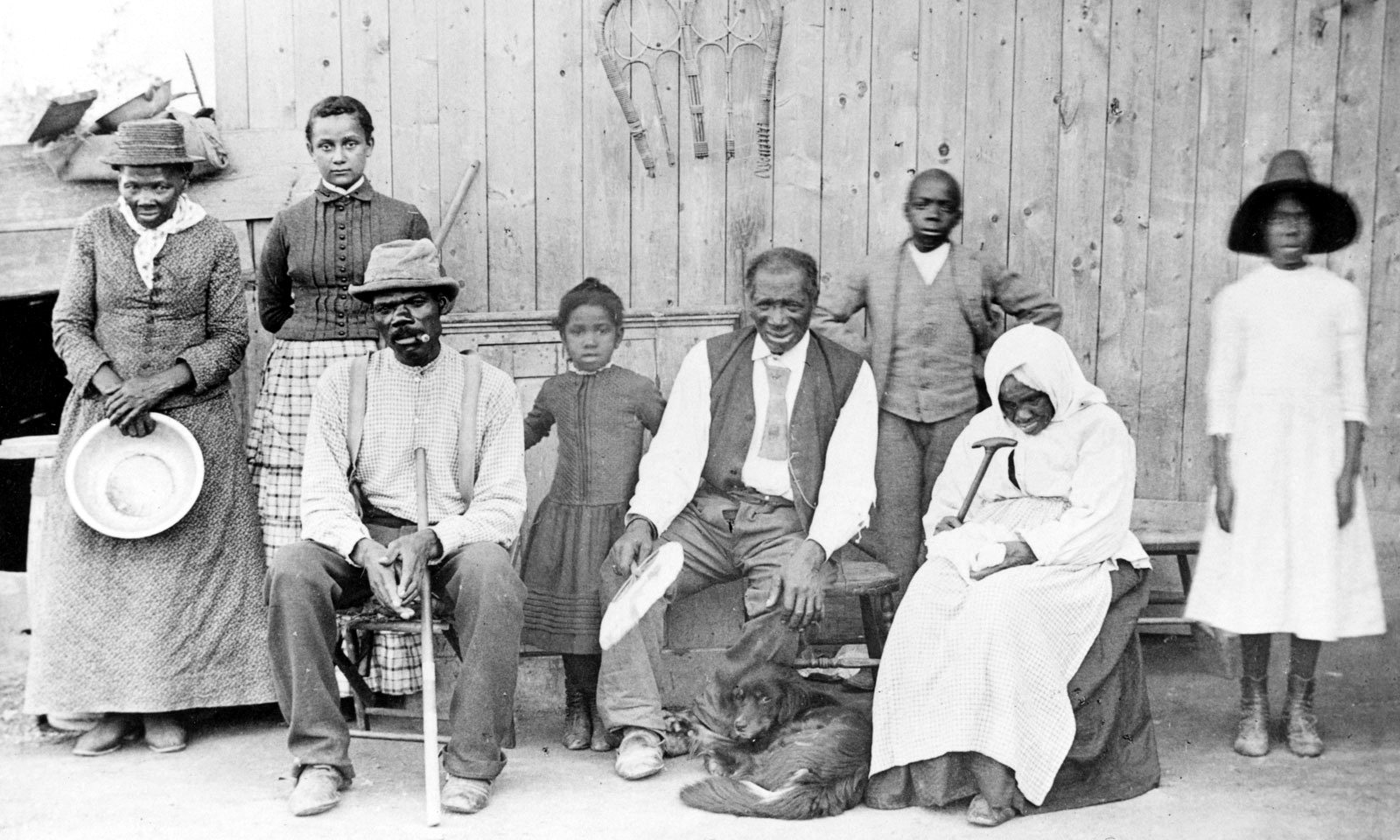

Voting has not always been a right for everyone in America, which is why for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, this right can hold a different meaning.

Nicole Hanson-Mundell, executive director of Out for Justice Inc. and a Marylander who was formerly incarcerated, said, “I should be determining my future through my vote and it should be like that for all Americans.”

Hanson-Mundell’s journey with voting began when she was a little girl and her grandmother would take her along with her as she voted. “As I became an adult at 18, I registered to vote and it was humbling for me because I had read all through my life that there were people who looked like me that did not have this ability.”

Throughout her life, Hanson-Mundell has felt strongly about the right to vote. She said: “I took a lot of honor in walking in an elementary school or church to cast my ballot. I got the opportunity to take my children in the voting box and pass on this generational tradition. But what was very troubling for me was that when I came home from jail, I lost that access.”

One in 16 Black adults who are of voting age cannot vote in America due to a felony conviction. But excluding Marylanders who are incarcerated for felonies from voting does not advance public safety. It is a token from our racist past that undermines the political power of families and communities.

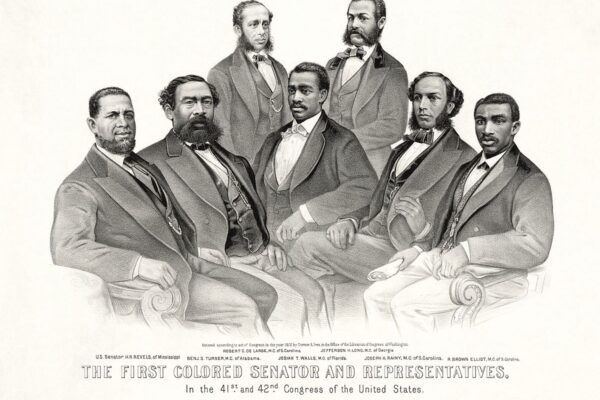

In fact, denying the right to vote to people who are incarcerated for felonies is a white supremacist policy that was intentionally created to block the political power of Black people following the legal end of slavery. It is a part of the ongoing structural racism that this country was founded on.

“When people don’t feel a part of something, when people don’t feel included in something, they don’t value it and they don’t respect it,” said Hanson-Mundell. “And so, if we want to ensure that we have a state and city committed to public safety then we will make sure that all people have access to the ballot.”

Cooper, Young, Hanson-Mundell, and many other Marylanders who have experienced or are experiencing incarceration and having their right to vote taken from them understand the importance and the power of voting. That is why they are leading the fight so that the promise of democracy and access to the ballot can be finally expanded to everyone.

“I should fight for liberty as long as my strength lasted.” –Harriet Tubman

This is part five of a five-part blog series to accompany ACLU of Maryland's documentary, Free the Vote.