300 Years Earlier: How Does the Legacy of Prisons and Policing Impact Black People’s Vote?

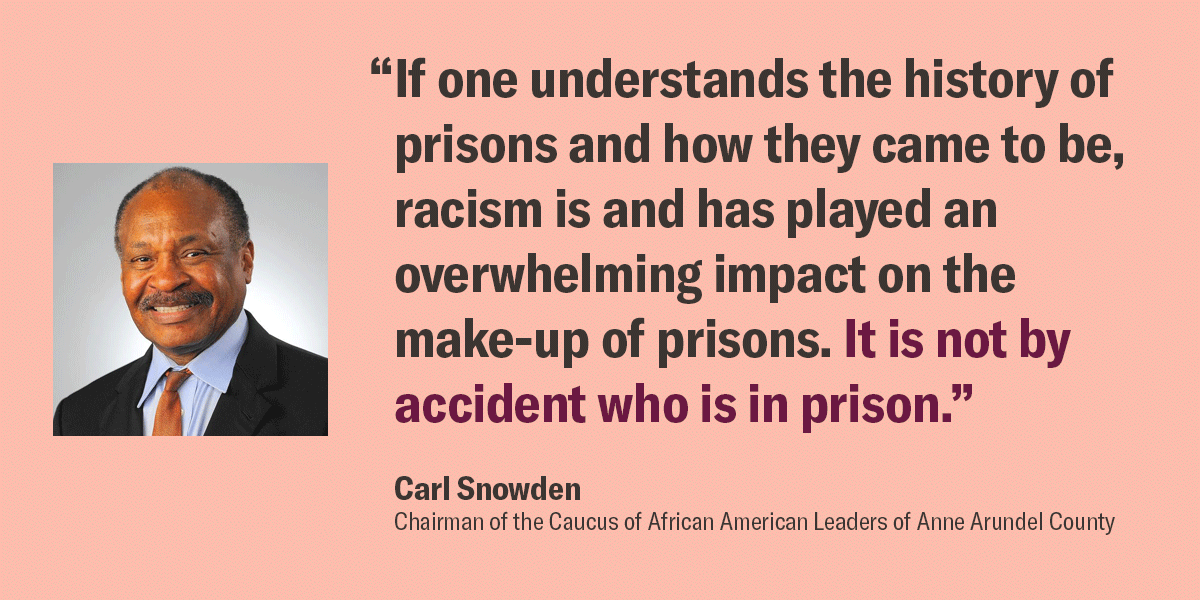

“If one understands the history of prisons and how they came to be, racism is and has played an overwhelming impact on the make-up of prisons. It is not by accident who is in prison.” – Carl Snowden, chairman of the Caucus of African American Leaders of Anne Arundel County

Out of slavery came the abominable effort to maintain white supremacy by blocking the political power of Black people through imprisonment, racist policing, and the then-novel idea of linking the right to vote to incarceration.

We can find the early origins of American policing as far back as the 1700s, when white people formed patrol groups to terrorize, beat, capture, and kidnap Black people, particularly those who sought freedom from enslavement. From its inception, the fundamental racism of that history continues in our present legal justice system.

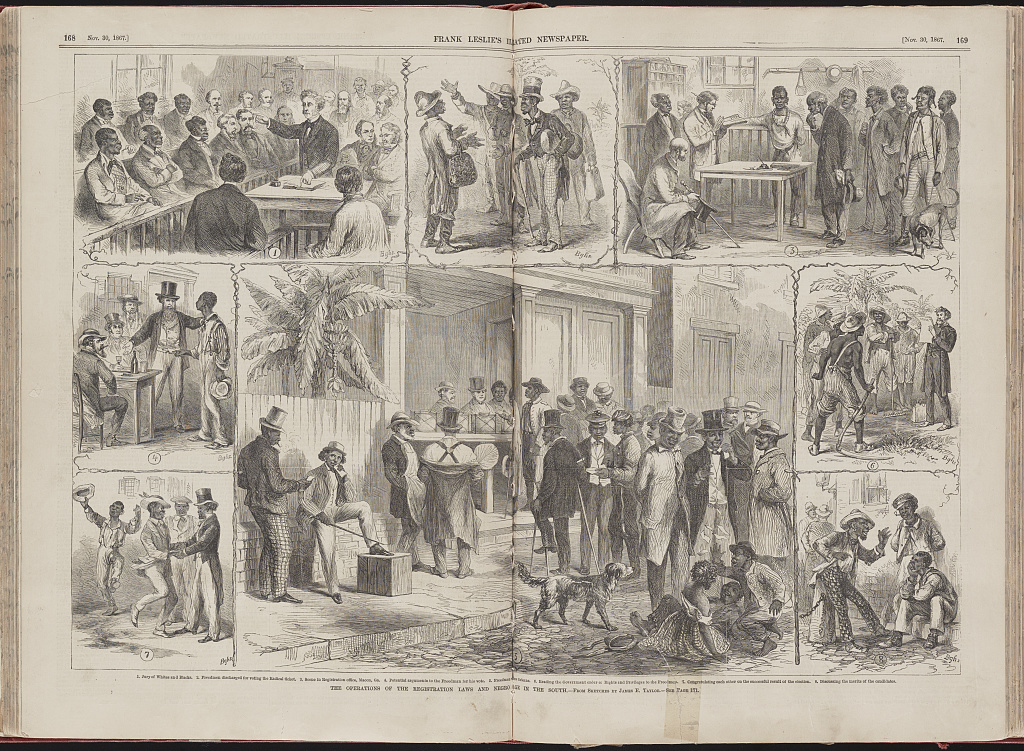

Around the 1850s, white men of the ruling class in the U. S. created “felony” disenfranchisement laws, which barred individuals who were convicted of a crime from voting. While this statute may not have been racially charged from the beginning, because Black people weren’t considered citizens and hadn’t yet gained the right to vote, these laws paved the way for the new idea of denying Americans their fundamental right to vote because they were or had been incarcerated.

Nicole Porter, director of advocacy of The Sentencing Project, said: “Confederate states that reconstituted themselves essentially used felony as a proxy for blackness with the intent to exclude Black residents from voting.”

When the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution passed in 1865, which included the clause that slavery could continue if for punishment for a crime, it created an economic and political incentive to lock up Black people to limit their political power and to continue forcing them to work without pay.

Jeffrey Robinson, deputy legal director of the national ACLU and director of the Trone Center for Justice, said: “Formerly enslaved people were arrested, convicted, and rented back to the people who owned them to do the exact same work they had done when they were enslaved. The south figured out we can maintain our slave economy simply by using the 13th Amendment.”

Immediately after the Civil War and after the 13th Amendment passed, Black codes were created to limit the freedom of Black people. “The purpose of Black codes was to essentially criminalize Black existence,” said Robinson.

These Black codes had their roots in slave codes. They attempted to permanently establish Black people as a cheap labor force after the legal end of slavery. Black codes also laid the groundwork for Jim Crow laws, which began in the 1870s and were a part of a white supremacist system to segregate, remove economic opportunities, and block the vote for Black people.

By imposing poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses on Black people, white people created barriers through a systemic, decades-long campaign of voter suppression. Grandfather clauses barred men from voting unless their ancestor had been a voter before 1867, and of course most Black people had been enslaved and not legally allowed to vote before then.

Here in Maryland, in 1870, the General Assembly unanimously voted against ratifying the 15th Amendment. This constitutional amendment said people could not be denied the right to vote based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude." But legislative leaders in our state tried to block it at the time.

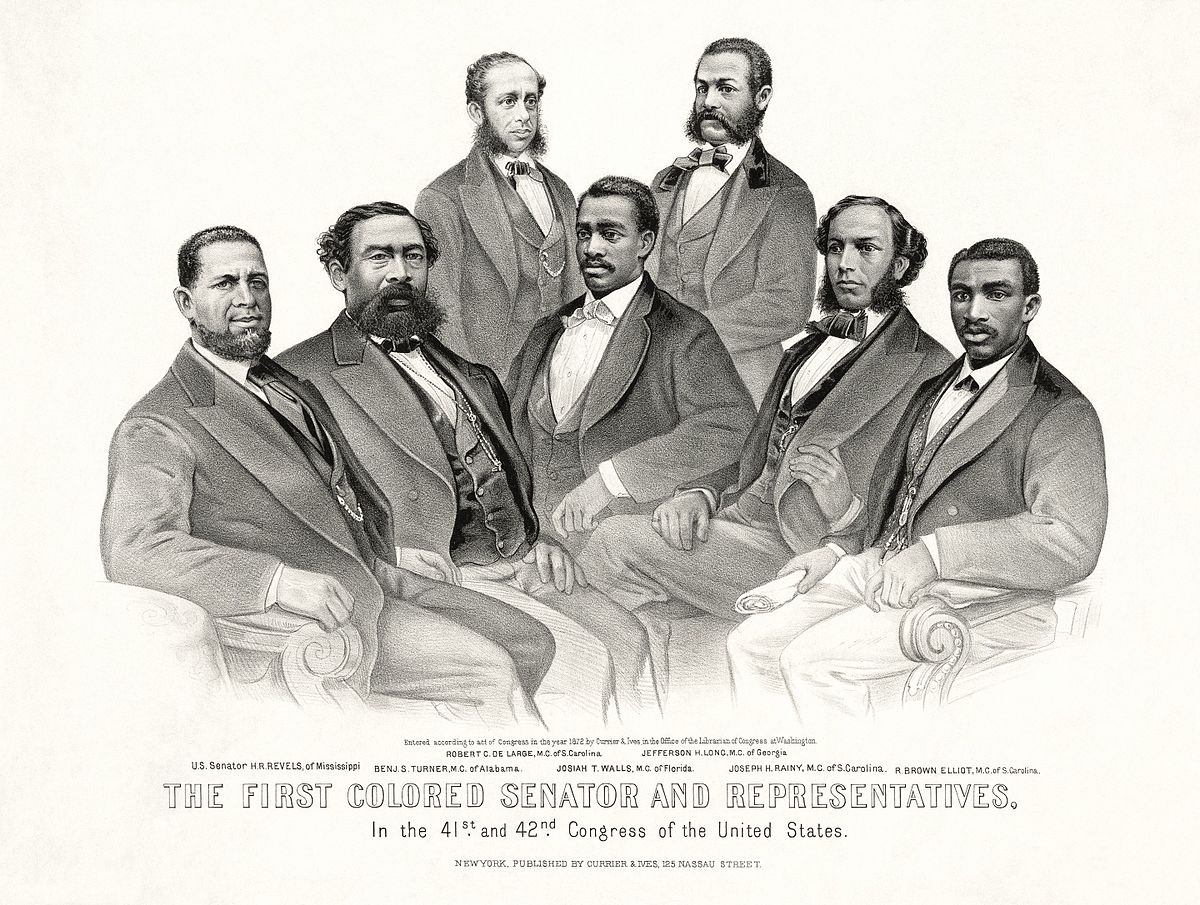

However, even after the 15th Amendment was officially enacted in the U.S., Black people voted and voted to elect many Black people in positions of power. Robinson said, “Over 2,000 Black men were elected into political offices. The second our community got the vote we knew exactly what to do with it.”

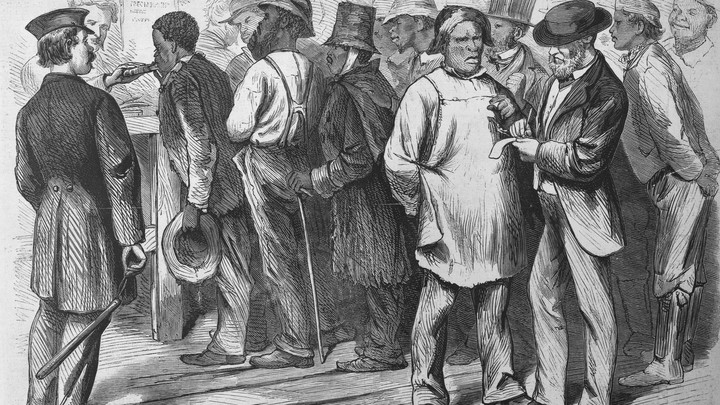

But in the 1870s, what followed when Black people exercised their right to vote was political backlash from the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists with the collusion of white people in power. The KKK kidnapped, murdered, and lynched Black people to keep them from voting. In addition, white people would also attempt to criminalize Black people to stop them from voting.

“There is an immediate effort to dredge up prior convictions and prior criminal activities by these men and use them to stop them from voting,” said Pippa Holloway, Professor of History at the University of Richmond. White people would actually whip Black people so that they could be identified as “criminals” who could be blocked from voting, too.

Holloway said: “There is an even more astounding trend in a number of southern states. Probably the most spectacular of which is North Carolina, in which they actually round up formerly enslaved men and whip them right before the election. Whipping in those days was punishment for a crime. They cut through the trial, accusation, and conviction and went straight from picking people up and whipping them and saying, ‘You have been punished for a crime. Therefore, you can’t vote.’”

Through this targeted legal oppression, coupled with intimidation and lynchings, white people made it almost impossible for Black people to vote for nearly 100 years.

It was also around the 19th century when modern policing began and our prison system was established. Motivated by the drive to control and oppress, the police were initially charged with targeting and arresting Black people, which we still see playing out today.

By the 1900s, Black people made up the majority of people incarcerated in the South, despite the fact that Black people made up only around 20 percent of the population at the time.

From the beginning when slave patrols targeted and abused Black people to when prisons were first created and mostly jailed Black people, our country created institutions that systematically abused, killed, and jailed Black people, while simultaneously taking away their economic and voting opportunities.

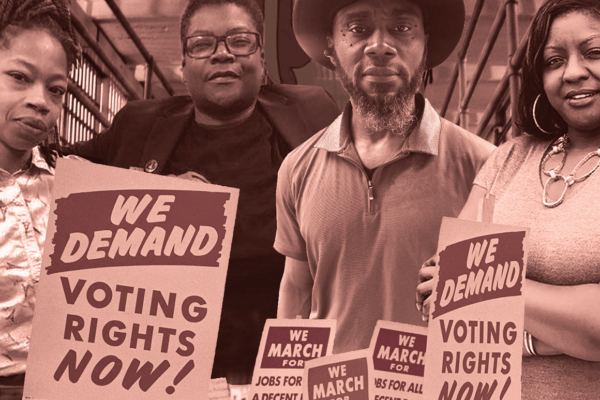

Despite all of these obstacles, Black people fought back through marches and protests and were even arrested and killed, in their fight for the right to vote.

“Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” –Frederick Douglass

This is part one of a five-part blog series to accompany ACLU of Maryland's documentary, Free the Vote.