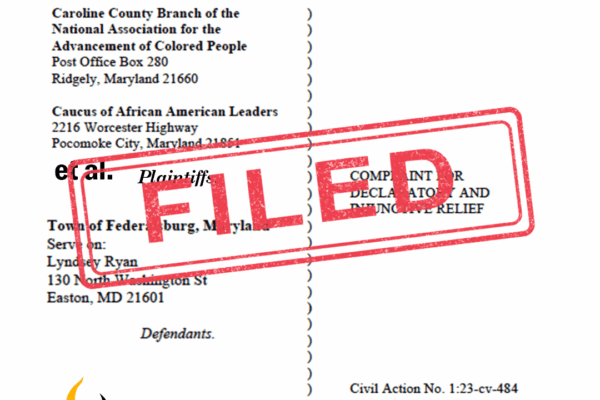

Federal District Judge Stephanie A. Gallagher ordered the Federalsburg town government to produce a new plan by May 23.

Video transcript availabe here

For 200 years, no Black person has ever been elected to the Federalsburg town government. Sadly, in some corners of the Eastern Shore like this, lives a racist legacy of diluting the influence of Black voters, suppressing Black candidacies, and preventing residents of color from electing their chosen representatives. This continuing legacy of a disgraceful era cries out for change. The people of Federalsburg are advocating for that change 200 years – in the making – by challenging the election system as a violation of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965.

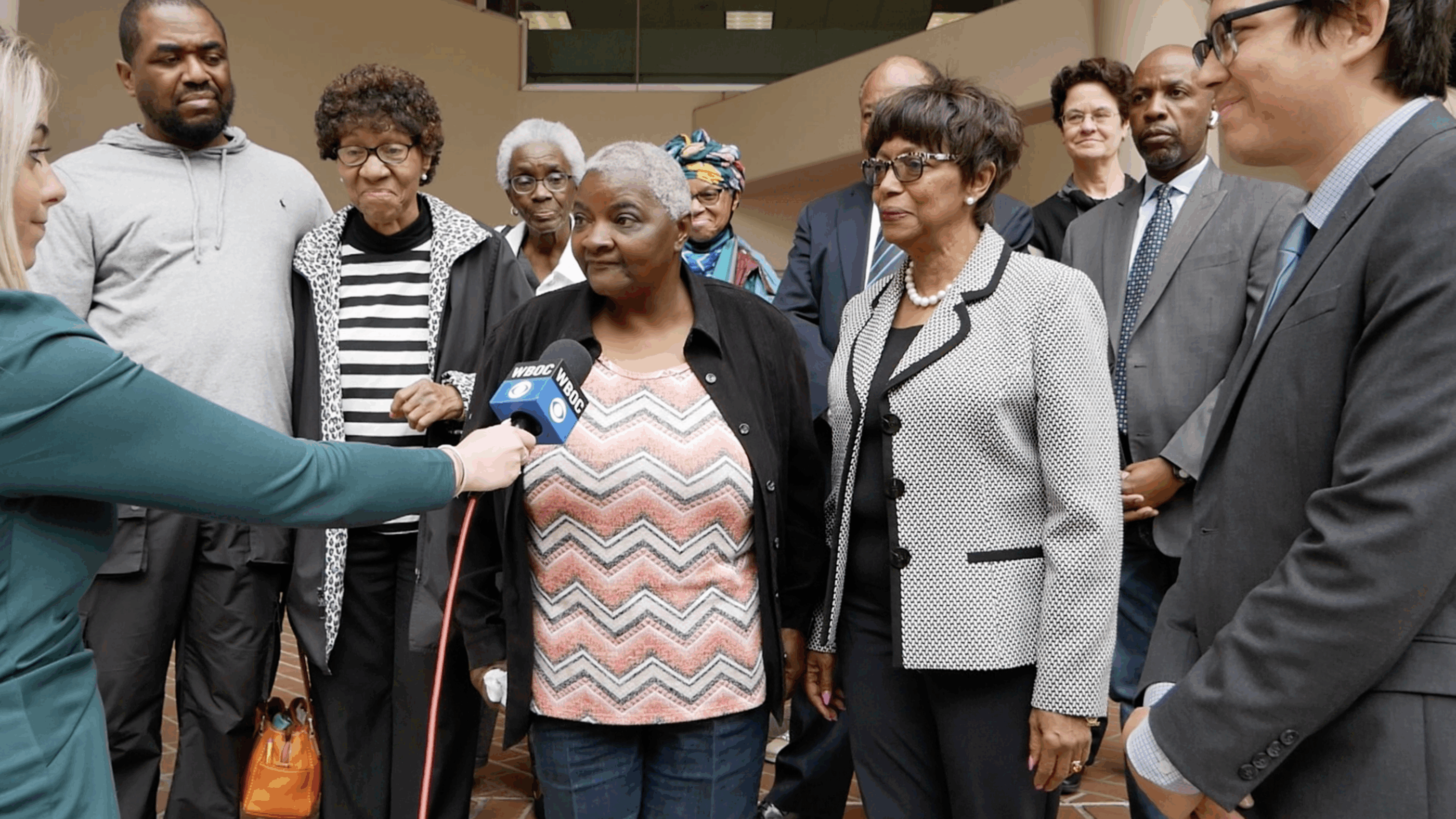

Sherone Lewis grew up in Caroline County and is raising her children there. She doesn’t see herself or her family represented in the Federalsburg Council and is demanding that the Town do what is right and change the system.

Sherone Lewis said: “It is so incredibly important to have representation after not having it for 200 years. Two hundred years is too long, and what an opportunity it would be to finally have Black votes count, and to at last elect someone who could really address the needs of the Black members of this Town.”

Currently, Federalsburg is half Black and half white in general population, with white people holding just a slight majority among voting age population. Yet, the at-large election structure used by the Town submerges Black people’s votes in the larger pool of white voters, completely blocking their ability to elect their chosen candidates. Through staggering elections so that only two of the four council seats are contested at a time, combined with a system where white voters consistently vote as a bloc to submerge Black residents’ preferred candidates, there is no way in which Black voters can choose their candidates or have their voice heard the way white residents do.

Darlene Hammond, a well-known and well-liked resident of Federalsburg, decided to run for Town Council, but she ultimately lost to her white opponents. The Town Council forced her to jump through hoops to run. For example, just two weeks before the election, the Town announced that there would be a public platform where the candidates would have to speak in front of an audience. Darlene Hammond had not heard of any similar event in any prior election, and no similar event has been held in any election since.

Moreover, several white candidates were permitted to declare candidacies at the last minute. These last-minute changes were made most likely to prevent her from winning the election. During her speech, the white audience was noticeably taken back by her mere mention of bringing diversity to the Council. Hammond said, “I would not consider running for office again under the current election system.”

Even though Black residents of Federalsburg have pleaded with the Town to remedy the problem and have repeatedly expressed their willingness to work with them to fix this blatant legal violation, white officials have resisted any true collaboration, repeatedly resorting to doing things the way they always have. Now, the federal district court in Baltimore has ordered the Town to come up with a racially fair plan to remedy the voting rights violations committed by the Town.

There is a collective longing for Black representation in government in the close-knit Black community of Federalsburg. Two-time candidate Roberta Butler, a lifelong resident of Federalsburg whose family has lived in the community for generations, gives voice to the collective hope of her Town’s Black residents.

Butler said: “It is my dream for someone from the Black community in Federalsburg to be elected to the Town Council. Without representation, nothing will change for the Black residents of Federalsburg. We are a part of this Town, and we need a voice in our Town government. I would like someone who looks like me, talks like me, and thinks like me to be on the city council. When I was running for Town Council, members of the Black community were hopeful and excited.”

Sherone Lewis echoed this, too, saying, “Having people who represent me and understand Black culture, having faces that look like mine in positions of power, having my voice understood and respected; these things would make me feel more like I am a part of Federalsburg.”

What are some other discriminatory practices still in place that dilute the Black vote in the Town of Federalsburg?

Polls are always located in a white area of town – currently in the Town office, a once-racially segregated movie theatre where Blacks were allowed only on the balcony. There is a lack of communication regarding basic information about the Town’s elections, including where the election will be held and who the candidates are. Finally, the Town’s use of odd-year, stand-alone municipal elections every two years, rather than coinciding with presidential or statewide elections is confusing and depresses voter turnout.

When we dive into the history of the Town, we find how the past informs the present. In 1619, tens of thousands of Black people were kidnapped and brought to the Eastern Shore to be enslaved. Leading up to the Civil War, many communities in the Eastern Shore profited from the racial caste system and were reluctant to join the Union.

Even after the Emancipation Proclamation, life on the Eastern Shore was slow to change, if much at all. Postwar, “Black codes” and eventually Jim Crow laws kept wealth, power, and resources in the hands of white landowners. For decades, white supremacy in the Eastern Shore inhibited Black people’s housing, education, and employment opportunities.

The legacy of slavery in this way lives on. We see it today in the form of effectively segregated restaurants, theaters, schools, and hospitals with Black and white people still living in two different worlds. To this day, Black people often remain largely absent from government, business, and civic life and are hidden in the background, particularly in Federalsburg.

Longtime civil rights activist, Carl Snowden, Convenor of the Caucus of African American Leaders, said, “Black residents feel unrepresented and disconnected from their government, as if the white officials who run the Town don’t care about them and scarcely even see them.”

Black people in Federalsburg experience a poverty rate that is about two and a half times the poverty rate for white people. Nearly one-third, 30.3%, of Black people live below the poverty line, as compared to 12.2% of white people in Federalsburg. Black median household income is $28,427 – about 60% of the $47,411 median income of white households. And just 9.3% of Black people in Federalsburg are employed in management or professional occupations, as compared to 24.1% of white people. This is unacceptable and yet another reason Black people need representation in their government to raise the profile of their concerns and help fix them.

Elaine Hubbard grew up with segregated schools, a “whites only” swimming pool, and a movie theatre where Black people were allowed to sit only in the balcony, which is now the Town’s office and where Town officials put the polling place. Hubbard said: “I want everyone in the town to feel as though they are on the same, level playing field. That’s not possible without representation.”

Currently, residents still face racism in their town. Butler recounted a story of the Town seizing her grandparents’ property. She was told to keep her “chin up” and endure as she was shunned and taunted with racist phrases during integration efforts. Lewis noticed as well, Black people having to “endure” racism, when her maternal grandfather, who generally had a powerful presence, would shrink in stature in the company of certain white people in the community. She noticed he was called “boy” by his boss. This racist culture is not in the past. It is still deep within the minds of even the Town’s youngest generation.

A white Federalsburg resident jeered at Lewis’s child, asking where “n-word drive is” and her daughter had to endure unwelcoming touching of her locks in school, where a Confederate flag can be seen from the high school. One of Johnson’s children was given cotton and cotton seeds from his teacher, and in another instance one of her son’s teachers grabbed him by the collar. Her youngest child was hit by a school officer and there was no accountability nor consequences for that officer. From their children being called an n-word to property being confiscated, Black residents living in the Town have endured racism and the denial of their voice heard in their government for 200 years.

Lywanda Johnson, mother and plaintiff in the case, said: “Having a Black elected official would alleviate some of the stress I experience living and raising a family in Federalsburg. I want equal opportunity, and for someone to level the playing field so that I can achieve the dreams I have for myself and for my children.”

Now is the time to rid the Town of Federalsburg’s at-large, staggered term election system and implement a racially fair election plan in time for the scheduled 2023 elections. After 200 years, Black representation is long overdue.

Recently, on May 9, 2023, a U.S. District Judge ordered the town of Federalsburg to submit a new plan to the Court and plaintiffs to fix its racially discriminatory election system. The Town had two weeks to secure Black people’s voting rights in Federalsburg and unlock Black candidates’ ability to run and be able to win. The community has advocated diligently for this moment.

Sherone Lewis said, “When they asked me, ‘What would representation on the Town Council mean to me?’, Choking back tears, I said, ‘It would make my grandparents proud, and it would make my mother proud. It will make my children proud and my grandchildren to come.’”